Sometimes a risk consultant doesn't know whether to laugh or cry. Or both.

The word "probability", in English as well as in Romance languages, comes from the Latin verb "probare", which means "to test or inspect" (it also can mean to prove/demonstrate, or approve, but that seems to be in different contexts).

In my mother tongue, Czech, the word is "pravděpodobnost", meaning "similarity to the truth", probably inspired by the German "Wahrscheinlichkeit", the property of giving the appearance of trust, or being likely to be true. I am told that in Hindi it is, "संभावना", more about chance or possibility than verifiability or truth. As I work with clients around the world, I'm not sure there's a clear correlation between cultural background and the natural preference to consider probability from a frequentist of subjectivist perspective, but I'm pretty sure linguistic connotations matter. A while back, I did an interview for Will Bachman's Umbrex podcast, "How to survive and thrive as an independent professional". He's recently kindly posted a transcript, which includes the transcriber's well intentioned but hilarious mis-hearing. My book project, "Be Your Own Risk Manager", got turned into "Veer On, Risk Manager!" -- which some would say is a pretty accurate verb for risk management, especially around the 2008/2009 crisis. Cynics would say even now! Full transcript below.

Happy New Year; had a busy fall and I see I didn't get around to posting.

Two upcoming conference presentations this month, in both of which I'll focus on parallels between the private and pubic sectors with an emphasis on risk management on organizations that straddle that dividing line in terms of governance, and therefore decision processes and risk appetite.

The request was innocuous and not atypical. Can you help our company develop risk reporting, and put in place a "small risk function" to drive it? Sure, mature risk organizations frame their raison-d'être more broadly, but many successful risk programs have as their genesis a request for better risk reporting.

However, further detail (through an intermediary) was not encouraging. The risk function was to organizationally report to the head of public relations, so as to stay "on message" with stakeholders. Not exactly what a risk professional brought up on a diet of risk management independence, three-lines-of-defense is keen to hear. I nearly declined to initiate discussions, suspecting strongly this might be a perversion of risk management into risk whitewashing instead. But, a couple of conversations later, we're reshaping it into something that does make sense. It's a company that has been stuck in deterministic, head-in-the-sand, don't-ask-don't-tell thinking. Stakeholders are getting restless, and when they're not getting good answers to their risk-related questions, supplying their own, less-than-perfect answer. Not clear yet if there is a professional collaboration to be had, but we've progressed to a much more mutually satisfactory conversation about how to pragmatically start having a top-management-and-stakeholders dialogue about risk, not focused on staying "on message" but instead broadening the message. For me as consultant, it's a good lesson in humility. Just because the initial framing of the issues rubbed uncomfortably on some core tenets of risk management as conventionally framed doesn't mean there isn't a meaningful opportunity for better engagement with risk and uncertainty. [Another excerpt from my book. A bit unpolished, but sharing as-is since I've seen several companies falling into this trap recently. Footnotes have ended up just pasted in smaller font with FN: before them] In [a previous section, not included in this excerpt], we discussed the usefulness of considering a range of expert opinions — predictions, if you will — for important drivers of uncertainty in your business. We also discussed the benefits of bringing experts together, and engaging in a dialogue about the rationale behind their opinions. We even discussed formalized techniques where the dialogue is interspersed with iterative polling, to see whether the discussion increases consensus or hardens into concrete lack of consensus that can underpin useful alternate scenarios to consider. Unfortunately, there is the old saying, “if all you’ve got is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”. Thoughtful executives who decide to bring probabilistic thinking to their decisionmaking routinely tend to abuse expert polls like this to bootstrap a probabilistic range in a flawed way. Consider the example in the following table, showing the range of near-term Canadian to US dollar exchange rates forecasts published by major Canadian banks in late February 2018. These numbers represent the expected (or in some cases, most likely) exchange rates from the banks’ models, which are often quite complex and based on various macroeconomic, financial (e.g. interest rate), and momentum/sentiment-driven indicators the banks monitor or predict as well.

An executive needing to stick in a base-case assumption into their short-term financial plan could do a lot worse than to put in the average or median number from these figures, or even just consistently use the prediction of one bank they have chosen, without cherry-picking. But suppose they have now “got religion” about probabilistic thinking, and want not just a point-estimate single base case prediction, but a probability distribution, or at least error bars on the base case estimate. They have a hammer - probabilistic thinking - and see 6 nails: 6 bank estimates.

It seems beautifully set up to do something like the following: throw out the extremes (1.21 and one 1.30 for Q2) as potential outliers and create a range from the rest. “The dollar will most likely be between 1.22 and 1.30”. Or do something mathematically fancier, like calculating quartiles [FN: In this case, this yields roughly the same range. By the way, there are different algorithms for calculating quartiles and other percentiles; if you really want to do this, you should for instance read up on the difference in Excel between the QUARTILE.INC and QUARTILE.EXC function. But in this instance, the issue is elsewhere.] from the “sample” and using them as whiskers around the median: “P25/median/P75 = 1.22/1.26/1.30”. This is, however, alchemy. It looks impressive, but is meaningless. Each of the banks’ estimates is in itself the expected value of their respective probability distribution of the outcome. They may not have actually calculated it probabilistically, or even refer to it in that way, but implicit in their prediction is a sense that this is the “best single guess” that balances out reasons it might be lower or higher. It systematically averages away any thinking they may have done about plausible ranges of outcomes. If you’re not persuaded, think of this thought experiment. Suppose there were only one bank, which as a result of its internal deep analysis decided the dollar was exactly equally likely to have a value of 1.0 and 1.5, precisely. If asked for a single point prediction, it would be quite reasonable for the bank to say, “1.25”, the average. The alchemy described above would take that one data point as gospel, and say a dollar will be worth exactly 1.25, when in fact the analysis done would actually be saying 1.25 has zero likelihood, it’s either much lower or higher. This example is extreme, but layers of that type of thinking on a smaller level underpin each bank’s prediction. So - what can you do? First, looking at the range of predictions and using heuristics like throwing away the extremes and seeing what is left is a good *qualitative* indicator for the level of confidence you should have in any prediction. As it happens, usually the banks’ average predictions end up being fairly close to each other, within a couple of cents.[FN: The fact at this point in time they were not has hit the popular press, for instance https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/top-business-stories/crazy-as-a-loon-the-chasm-in-forecasts-for-the-canadiandollar/article38019810/] The fact the range is now 8+ cents is itself indicative of a greater degree of uncertainty. Second, if you can, go to the source (or to other sources) to gain a true range of predictions, ideally with scenarios and rationales. For a Canadian company at this time, it is much more important to understand *how low or high could the Canadian dollar plausibly go*, based on how different factors evolve. If you want, you can use sampling on scenarios to give you a range, in the manner discussed in Section [X.X]. As mentioned there, there are all sorts of biases associated with selection and weighting of the scenarios, but you are not falling into the trap of reducing the range of uncertainty just because you don’t see it. Third, look for something else than nails, and bring out your screwdriver or glue or whatnot. For instance, looking at historical US/Canadian dollar exchange rates, it turns out that about 20% of the time, the rate changes by more than +-5% of the time over a 3 month period. And on average every second year, over some 3 month period the rate jumps by about 10%. Some version of this type of analysis is probably more useful in terms of putting semi-probabilistic error bars around any chosen single prediction than alchemy on the range of banks’ expected value predictions. [FN: Warning: as discussed in [xxx], a bug as well as feature is that the outcomes of such analysis depend on the choices you made in structuring it. In this instance, it is based on looking at the ratio of month-end exchange rates to the rate 3 months previous, over the past 10 years. And the 20% figure refers to 10% of the time having a decrease of 5% or more, and 10% of the time an increase of 5% or more. Whether this is right framing to use depends on the business problem this is being applied to. For instance, the ideal analysis is different if the goal is to estimate how much quarterly financial results will be influenced by (unhedged) currency exposures integral in the business, compared to if it is to stress test how much could be gained or lost on a single contract that generates a revenue-cost currency mismatch open over a period of 3 months. That is outside the scope of this book.]

I'm making two upcoming conference presentations, both keynote speeches, one followed by moderating an executive panel. I will hopefully will be able to post material soon afterwards; contact me if interested earlier.

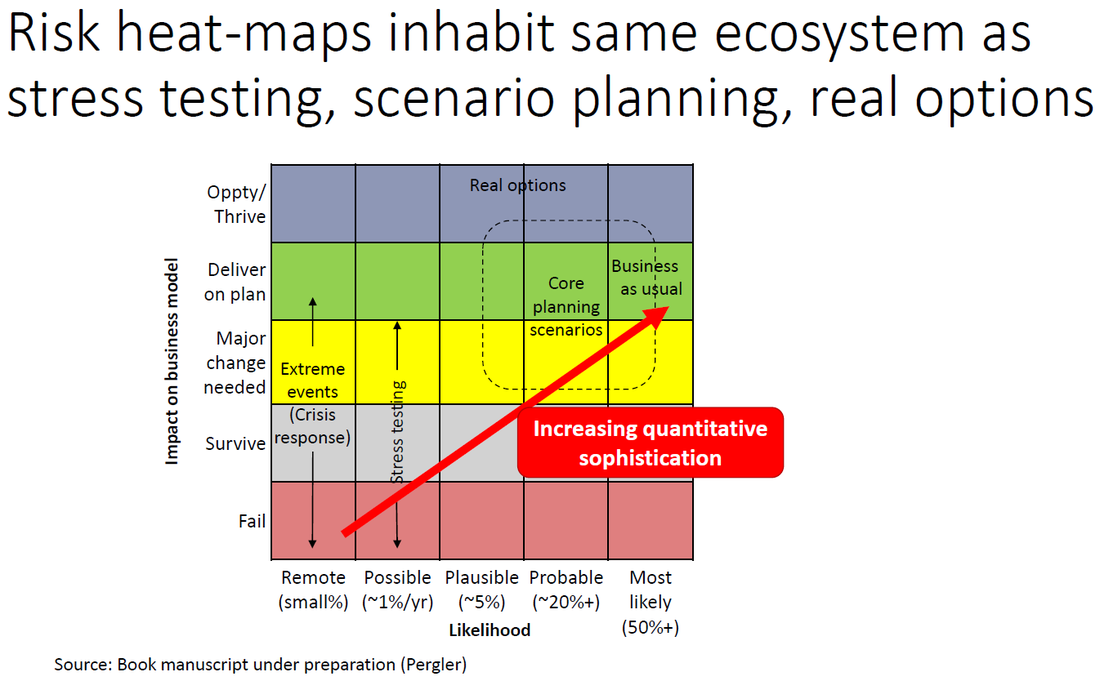

My former colleagues at McKinsey have just published an article on stress-testing for nonfinancial companies. Unsurprisingly, I very much agree with them. Whether the goal is stress-testing (a specific risk-management centred viewpoint) or strategic planning, companies need to think more in scenarios to effectively get their arms around the uncertainty they need to navigate.

I've written about this on these blog pages and in an article planned for a Canadian mainline business publication (where it ultimately ended up on the cutting room floor after internal conflict in the editorial board in which I was collateral damage) in the context of the election of Mr Trump as president. Ultimately, stress testing, scenario planning, and risk management live in the same ecosystem, just in different ecological niches. Ideally they work together, and which one is a priority to exercise for a given company, or provides the best path towards a more holistic approach, depends on the circumstances. |

Martin PerglerPrincipal, Balanced Risk Strategies, Ltd.. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © 2014-2020, Balanced Risk Strategies, Ltd. – Contact us

RSS Feed

RSS Feed